How many of us have been sitting somewhere on a dreary winter’s afternoon, looked out the window and thought, ‘There has to be more to it than this’ — or felt the impulse to leap up from where we’re sitting to stride off into some great adventure?

How many of us have been sitting somewhere on a dreary winter’s afternoon, looked out the window and thought, ‘There has to be more to it than this’ — or felt the impulse to leap up from where we’re sitting to stride off into some great adventure?

In 1971, Luke Rhinehart wrote The Dice Man — whose subheading announced, ‘This book can change your life’. One day, Rhinehart is inspired by an intriguing coincidence and, bored with his job, gives over his life to the idea of living by random options chosen by throwing dice. At first these are quite low-key … at least, as low-key as crawling to work in a tuxedo can be. But gradually, he gives his life over to an anarchic and amoral rampage …

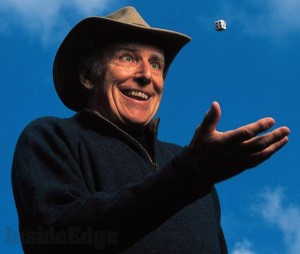

‘Luke Rhinehart’ was actually George Cockcroft — who, as a teenage nerd, started rolling the dice to break down his shyness and stuffiness as a scholarly youth, as a means to break habits and reinvent himself. The scholar went on to gain a doctorate in psychology and then wrote his novel (which posed as a work of non-fiction, apparently written as the autobiography of a successful New York psychoanalyst, Luke Rhinehart) as an explanation of how he discovered his dicing philosophy and the changes brought about by it.

‘Luke Rhinehart’ was actually George Cockcroft — who, as a teenage nerd, started rolling the dice to break down his shyness and stuffiness as a scholarly youth, as a means to break habits and reinvent himself. The scholar went on to gain a doctorate in psychology and then wrote his novel (which posed as a work of non-fiction, apparently written as the autobiography of a successful New York psychoanalyst, Luke Rhinehart) as an explanation of how he discovered his dicing philosophy and the changes brought about by it.

The Dice Man invites the reader to think about how their life might be if left more to fate and chance. While the author was teaching psychology, he posed the same question to one of his classes — asking them whether the ultimate freedom might lie in making all decisions randomly. He said the use of the dice was a means of challenging the ego and allowing experimentation with the self. As a man who was shy of women, he admitted it was through using the dice that he was able to find a wife.

‘I was driving my car out of the hospital grounds when I spotted two attractive nurses, but being an inhibited chap at that stage of my life, I drove right by them. Half a mile up the road, I resolved to stop the car and consult the dice. If they fell on an odd number, I would go back and try and pick the girls up. They fell odd, so I drove back and offered them a ride. They were on their way to confession, but the church was closed, so I invited them to play tennis the next day. All through the game, I couldn’t help noticing that one of the women was tall, long-legged and full bosomed. Eventually I married her.’

People are desperate for change, ‘Rhinehart’ says. They’re never satisfied with who they are or what they’ve got, and are trapped by constrained thinking. Life too easily becomes a pattern of routines, he adds, insisting that life is too precious to allow it to drift, and to allow habit to dictate, as we make the same kind of decisions again and again. More dangerously, he felt, we become slaves to the perceptions of social convention. He believed religious dogma to be equally dangerous — when others impose on us their view of what their god is supposed to have said — when we allow people to present morality and belief as textbook certainties that demand blind faith, obedience and adherence.

The Dice Man attracted a cult following that lived by its philosophy. It was a controversial work, seen by many as provocative and dangerous — and was obviously denounced by many religious organizations. Nowadays, the book that was once named ‘novel of the century’ by one magazine is selling in greater quantities and in more countries than ever before — a fact that still completely mystifies its author.

We could all begin the dicing lifestyle right now and write out and prepare a list of options, right this minute … ‘I will not watch TV or read any newspapers for one week … ‘I will live on a diet of prunes for a year’. For his part, Rhinehart lists five golden rules for betting on your life’s decisions …

1) Don’t list an option that you would be unwilling to try to do.

2. Remember, a losing bet could just be the gods of chance setting you up for a bigger winner.

3. Always list one long shot as an option, because in life one successful long shot can transform everything.

4. Every day cast a die to determine whether or not you gamble that day.

5. Periodically ignore every one of the previous four golden rules.

Ultimately though, you have to ask who or what in me (who or what in Rhinehart) chooses the options in the first place. We can’t control what we’re going to think, before we think it. When a thought appears, we may choose to act on it, or not — or, in this case, choose whether or not to put it on a list of options. But it’s never going to be truly random— as a choice has to be made about what goes on the list in the first place.

The Dice Man reads like an account of the Trickster archetype having a field-day. But behind all the amorality and chaos the author is saying that rolling the dice offers a way into a new identity. He says that, everyday, we should make a conscious decision to tell one deliberate lie — not to encourage deceit or to harm others, but to push us into new areas where we’re forced to live by our wits and think on our feet … to give us a new perspective on ourself. Underpinning it all, there’s a sense of a man struggling to find a way to wake up and remember his true identity, who and what he really is — something that really would change his life.

[Extract from my upcoming book Another Roll of the Dice.]

14 Responses to A Roll of the Dice